By @JustinWetch

The Brother's Gift

Yudho got into the number one art university in Indonesia, and then his father told him they couldn't pay for it. The tuition was beyond what the family could manage. He was heartbroken, ready to abandon the path before it started. Then his older brother stepped in, worked hard, and covered the cost. That gift made everything else possible.

Yudho had loved drawing since childhood, filling his school notebooks with sketches until his mother had to keep buying replacements. He didn't even know you could study fine art in college until someone told him. Once he was in, he painted everything. Realism, abstract, political pieces, personal pieces, jokes. He produced nearly 300 paintings in a single year because he was young and didn't know what his subject matter should be yet, so he just celebrated the possibilities, bombarded with inspiration and unwilling to narrow it down.

"I felt I was too young to pick something serious," he says. "So I drew everything."

After graduation, the Indonesian art market had cooled on young painters. Nobody was investing. Yudho pivoted into design and branding work to survive, and for nearly a decade that's what he did, moving between studios and offices, occasionally confronting bosses for raises just to make rent. He was good at it, helped build brands that still thank him today, but it wasn't painting. It wasn't the thing he'd been given the chance to do.

Speaking to a Mirror

Something strange happened during those design years. Whenever Yudho picked up a paintbrush, he would start crying. Not from sadness exactly, not from any emotion he could name. It just happened, tears arriving without explanation, and it confused him for a long time.

Years later, he understood. Painting in isolation was like speaking to a mirror. There was no one on the other end. The act of creation without community, without exchange, without someone receiving what he was trying to say, left him hollow. Art made alone felt incomplete, a monologue into emptiness.

When he joined the NFT space in 2021, that melancholy vanished. Suddenly he was connected to other artists, to collectors, to people who responded and engaged and shared their own stories. He never felt that strange sadness again.

"I realized I make art to communicate," Yudho says. "About my emotions, my stories, my concerns. Art can be made for art's sake, but artists make art to communicate."

Blessing in Disguise

In 2023, Yudho's computer was hacked and his crypto wallet seed phrase stolen. Everything he'd built in the NFT space, wiped out. He went to his wife and asked if he could start over from zero. She said yes.

The setback became a gift. With time to reflect, Yudho realized the landscape had shifted. AI art had exploded, and mid-tier digital painters like himself were being outpaced, too slow to compete with machines that could generate images in seconds. A friend gave him advice that stuck: stop looking for something new, look into yourself and see what you already have.

He experimented for three months, mixing his digital painting skills with pixel art. If you scroll through his Tezos account from that period, you can watch the transformation happen piece by piece, not instant but iterative, each work teaching him something for the next. Eventually he committed fully to pixel art, and something clicked. Collectors responded. He responded. It felt, he says, like shaking hands with his audience for the first time.

"Making good pictures is not enough anymore," Yudho says. "You have to be more unique."

Dirty Pixels

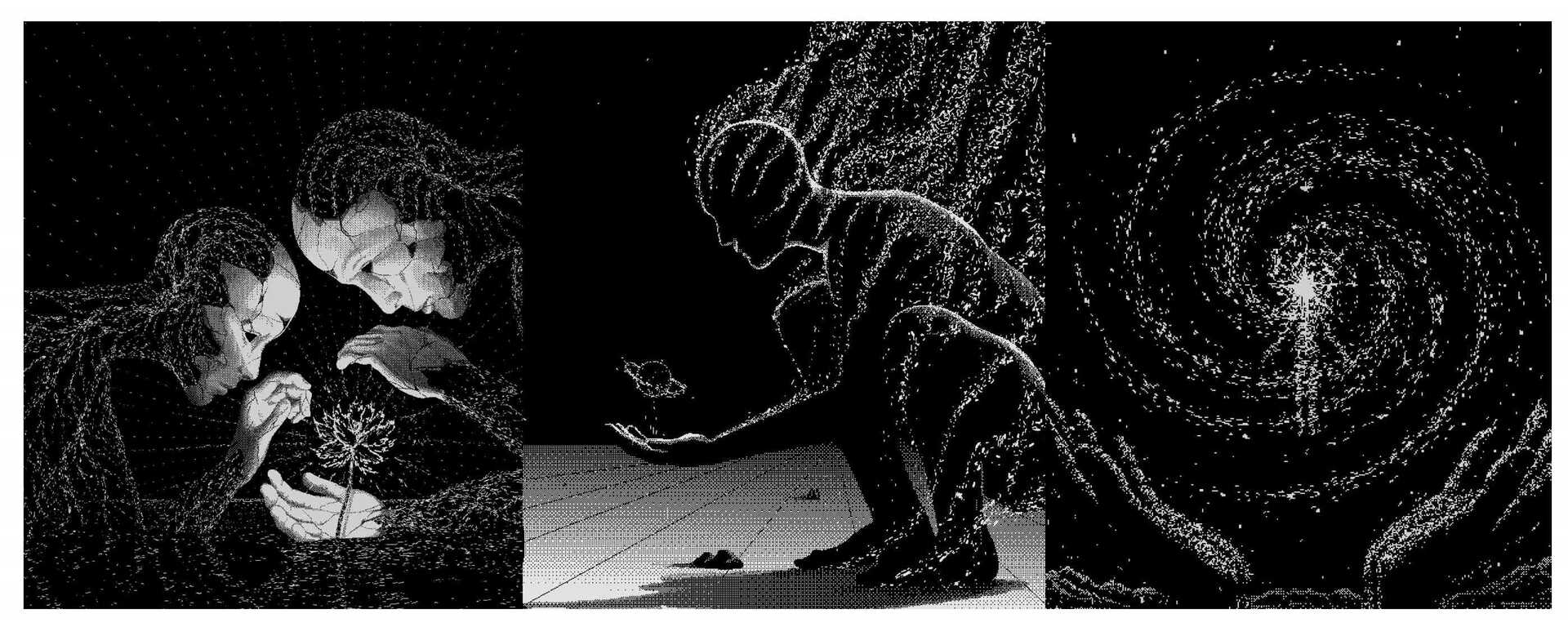

Most pixel artists make clean, meticulous work, every dot precisely placed into tidy compositions. Yudho tried that and realized he couldn't do it. He was too chaotic. So he treated pixels the way he once treated charcoal on paper, rough and raw, full of texture and motion, deliberately untidy.

He calls the style "dirty pixels," and the term fits. The images look sketched rather than constructed, alive with what he describes as "pointillistic noise," thousands of pixel points creating depth and atmosphere the way a charcoal drawing builds tone through accumulated marks. A pixel is the smallest unit in digital art, just as a point is the smallest unit in traditional drawing, so his work becomes a kind of chaotic digital pointillism.

His animations are hand-drawn, usually twelve frames that loop seamlessly. Because they're made by hand rather than generated by code or 3D software, they carry the imprint of his actual movements, organic and slightly imperfect in ways that make them feel alive. When he creates a piece that will have a physical counterpart, he builds the physical version first, so he can feel its presence in real space before finishing the digital animation. The tangible informs the virtual.

Schizo-Techno-Spiritualism

Yudho has a term for the philosophical tension running through his work: schizo-techno-spiritualism. It sounds like a joke, but he means it.

On one hand, technology can be a path to enlightenment. We can search for meaning, find our gods, ask an AI what's good or bad and receive something like guidance. In that sense, technology becomes a spiritual tool, maybe even a new kind of religion. On the other hand, technology can become an idol that enslaves us. Instead of finding God through tech, we worship the technology itself, surrender our freedom to it, become dependent in ways we don't fully recognize.

Yudho admits he lives in both states. He can't imagine life without the internet. When he's brainstorming ideas, he finds himself discussing them with AI, using tools like ChatGPT as a creative sounding board. He doesn't always know if he's choosing his ideas or if the AI is subtly choosing for him. The dependency is real, and it unsettles him, and it feeds directly into what he makes.

The Buddha figures that appear in his work aren't religious in a literal sense. They represent past wisdom, the accumulated knowledge of ages, now getting blurred and transformed by the modern era. His compositions often depict vast dark spaces, voids that could be the cosmos or the internet's infinite scroll, and somewhere in that darkness something appears: a figure, a flower, a moment of unexpected grace.

The Lotus

The lotus is Yudho's most personal symbol. It appears throughout his work, blooming in dark ponds, emerging from emptiness. Viewers can interpret it however they want, as hope or purity or whatever precious thing they hold onto in difficult times. But for Yudho, the meaning is specific.

The lotus is his family. It represents him, his wife, and their child. Something alive and beautiful found in darkness.

He tries to evoke a feeling that sits between peace and loneliness in everything he draws. The internet is strange that way, he says, so connected and yet capable of profound isolation. He suspects many people feel that tension, and his art seems to confirm it. Some have reached out to tell him his work stopped them from ending their lives. They felt seen, understood, connected to something when they needed it most.

"To me, that's when my art truly succeeds," Yudho says. "I make art to communicate, and if it makes someone feel that strongly, that's more than any sale."

The Wrap

Yudho shouts out his collectors: @drleenft, @cypherdao, and @tinoch.

Artists inspiring him lately: Sathar (@baladasathar), another great Indonesian artist. @0xdiid, creator of Efficax, an on-chain minting app. And @Uhcaribe, a Caribbean artist with vibrant work.

For future Weekly Dose episodes, he recommends the same three.

Yudho's advice: "Art is for everyone," he says. The dirty pixels keep moving, chaotic and alive, carrying whatever feeling he put into them out into the void, hoping someone on the other end receives it.