By @JustinWetch

This article was simultaneously published on X. Join the discussion:

Two Houses

Briscoe grew up in a house full of people who made things. His brother played music and painted. His sister danced ballet. His father dabbled in drawing and loved making cartoons. Creativity was ambient.

His parents never pushed him toward any of it. He tried music for a while. It didn't take. Photography stuck. His grandfather would send him war photos from the Marines. Something about the camera felt like a skill he could grow with.

But the real incubator was his father's house in rural North Carolina. No internet. No cable. Just exploring outside.

"At my dad's house we didn't have internet or cable. It was extremely inconvenient then, but I'm really grateful now that I'm older."

He spent summers skating, wandering, sitting with nothing to do. He resented it then.

"I think having boredom is important, and my imagination really sprouted from that."

His dad would let him watch serious films. Stand By Me. Pan's Labyrinth. Saving Private Ryan. Not to shock him, but to respect him. After the films, they'd talk. His father never talked down to him as just a dumb child.

"Children are a lot smarter than people think and very aware. They just can't articulate it."

The Crane Climber's Reckoning

As a teenager, Briscoe found an abandoned brick factory outside his neighborhood. He and his friends turned it into a playground. Light-painting with steel wool. Making fires. An excuse to push past the familiar.

When he got a car at eighteen, he started going alone. Construction cranes in downtown Raleigh. Night climbs. He'd perch above the city, invisible, listening to laughter from the bars below.

"There was this crane next to a strip of bars. I could hear everybody having fun down below. It felt like the perfect place to be, just as an observer."

The photos were striking. Long exposures. Places he shouldn't be. But after a while, he started to question them.

"I had graduated, I had stopped going to college. I asked myself, 'Am I showing anything special? There's more to me than this, more I'm feeling and trying to say.'"

The realization hurt. He looked around and saw countless photographers doing the same thing. Urban explorers with the same shots, the same angles, the same empty cool.

"I was pretty hard on myself. Like, there's a million of me. There's nothing special about what I'm doing."

That pain pushed him forward. He was terrified of being called cringey, of trying something personal and getting dunked on. But he pushed through anyway.

"You just gotta. You're gonna have to go through that phase, and I did."

He started studying other photographers. Learning their techniques. Building concepts instead of chasing accidents. The work shifted from single images to sequences. From cool shots to worlds.

"That starts to take shape and worlds start to build. Then you start to form a relationship with this world you're building. Like a city planner, you're like, 'This belongs here and this doesn't.'"

The Map Is Not the Territory

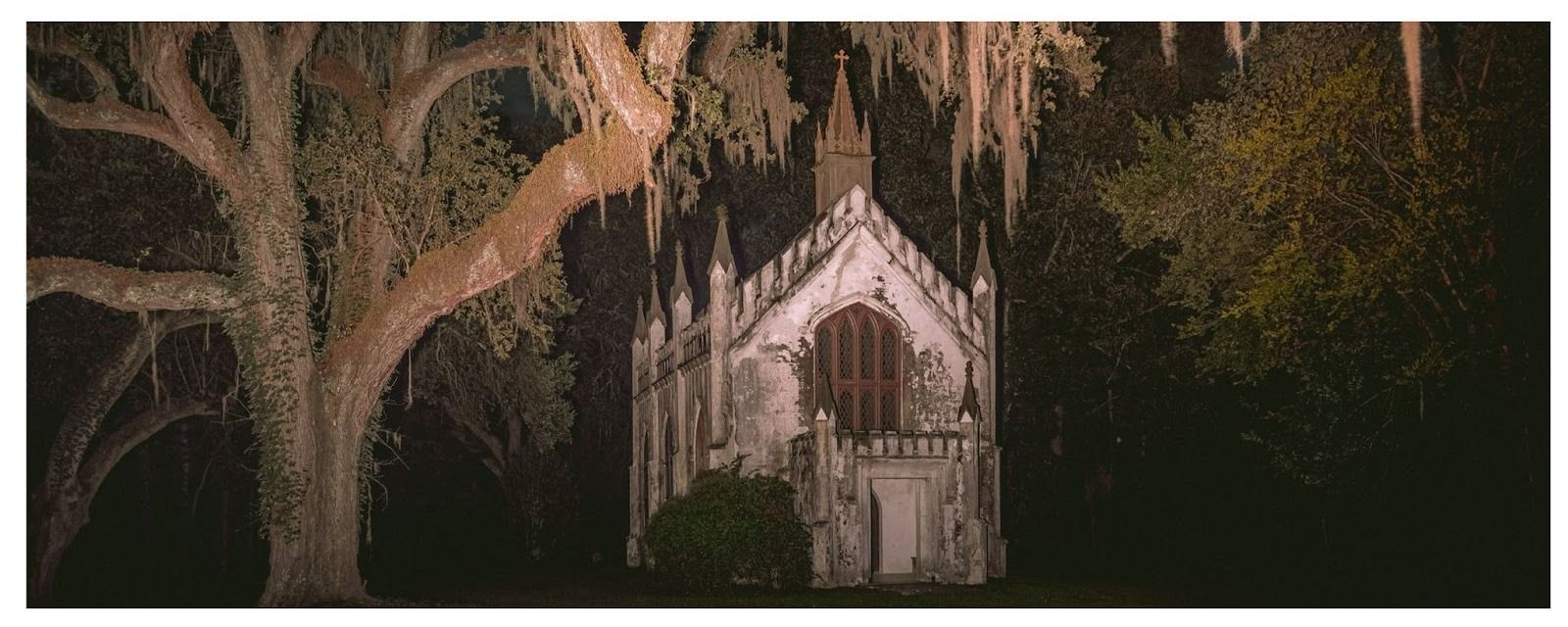

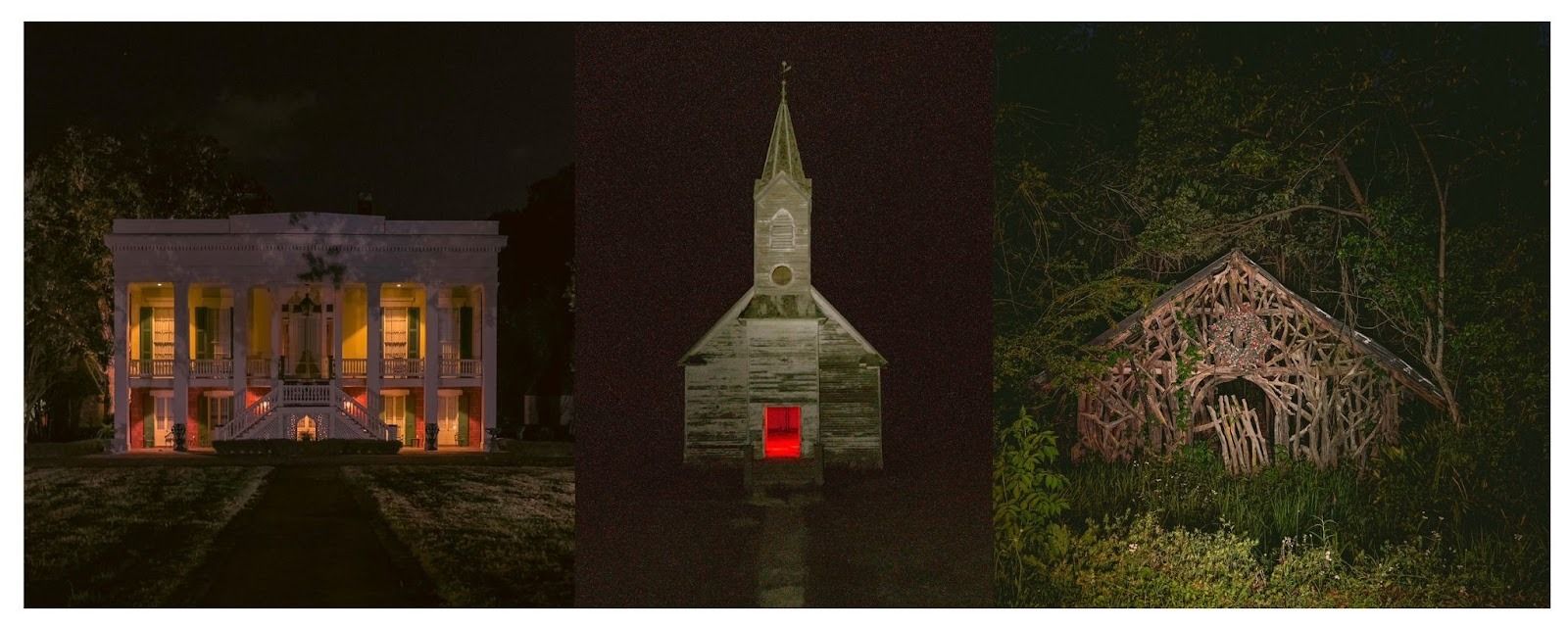

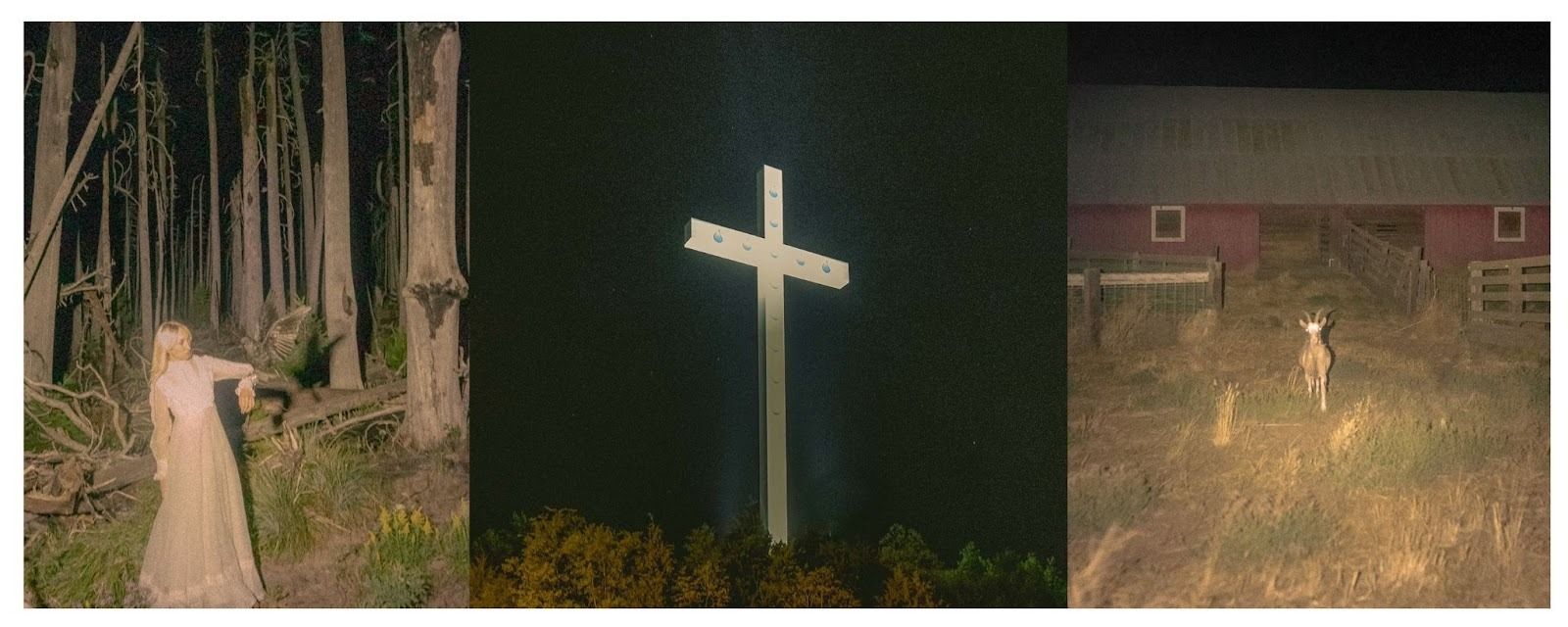

Briscoe's work is full of symbols. Churches. Animals. Specific locations in the Deep South. Recurring figures. He knows what they mean. He's not going to tell you.

"There's personal relationships and stories. Actual people that show up in the work. And my relationship with them, told through symbols and settings and moods."

He's careful here. He wants viewers to project their own feelings. To bring their own weight to the images. Explaining would defeat the purpose.

"When you talk about something that is special and divine to you, like a dream or a belief system, and you tell people about it, it loses its power. It loses its weight."

He references Bob Dylan. The idea that naming the sacred diminishes it. He doesn't want to use "the work speaks for itself" as a cop-out for laziness. His choices are deliberate. He's just not interested in handing out the legend.

The Town Turned Red

One of his series is called The Town Turned Red. It's about anger. The kind that consumes you if you let it.

"It was definitely about inescapable anger and rage that you no longer want to experience because it completely ruins your life."

He imagined a place where he could leave it all behind. A town to dump the fury and walk away.

"I wish I could put it all in a town and just leave it there.”

A deer appears in that series too. In his worst moments, in fits of rage, he wonders what his grandparents would think of him. The deer is a reminder. A way to catch himself.

"I just wish I was a better man, and I'm not. I'll remind myself that these people are here, or they're not here, or I spiritually wish they were here. Placing them in a photograph, I can catch myself and remind myself I'm not just this person I don't want to be."

The South as Muse

Briscoe used to hate where he came from. As a teenager, he made his hometown into a villain. A terrible, evil place he needed to escape.

Then he traveled. Saw the rest of the country. Came back.

"I spent so much time seeing the rest of the country and I was like, 'Damn, this place is fucking nice.' And I love it, and all those things I was complaining about are actually part of why I love it."

Everything he once resented became essential. The heat. The landscape. The way people live out on farms, doing their thing.

"It's just normal. My normal. And I don't want that to change."

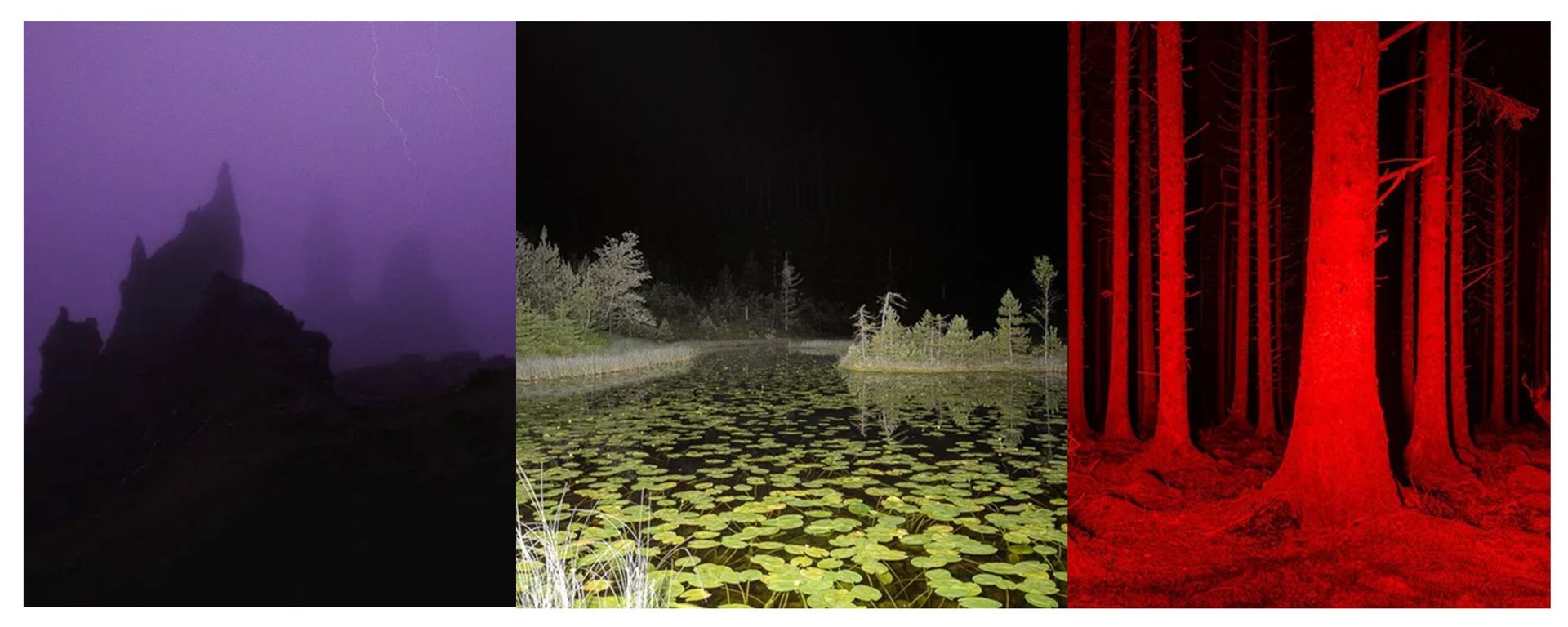

The South isn't backdrop in his work. It's character. Swamps. Churches. Barns with windmills and old cars. He shoots in the Black Forest of Germany because its folklore rhymes with his own obsessions, but he always returns home.

His move into film follows the same logic. The YouTube series Briscoe Park is off-limits for explanation. He wants it to run wild. But he'll talk about why motion appeals to him.

"Motion picture just offers a lot more room to have someone immersed and emotionally committed to an experience."

Photography hands the viewer an image and lets them decide what it is. Film gives the artist more control. Pacing. Sound. The ability to reward attention.

"If they're gonna watch anything I do, they're just going to pick up on things if they don't get distracted. Like, you're gonna miss some shit."

He used to be a purist about natural light. Then he realized that limited where he could shoot. A borrowed light bar changed everything. Now he treats photography like film. Mise en scène. Staged lighting. Every element intentional.

Arcana

Briscoe is releasing a photobook called Arcana. It compiles the majority of his completed series. A comprehensive anthology. Cohesive walkthroughs of entire bodies of work, all in one place.

"It's a way for everybody, over the years, to have everything in one place and to do a little more storytelling within that."

He's done a small book before. Nothing like this. The timing aligned with a publisher he admired. They'd made a friend's book and it looked amazing.

"We talked and hit it off. They were like, 'We want to do this work justice and preserve the love you have for it.'"

The Kickstarter funded in nine hours. He'd braced for failure. Prepared himself for the possibility that it might not get made.

"To have that goal met within nine hours and know that this book is being made and everybody's stoked about it. It's just super inspiring and makes me feel grateful that I shared with everybody and it was for something, you know?"

He's still processing it. Trying to stay present. Feel the gratitude.

"It's very overwhelming in the best way possible. Sometimes I feel a little undeserving of it, or just like, holy shit. Like this is a bit 'you're too nice.' I just don't have the fucking words for it."

The Wrap

Briscoe shouts out Max Karlan ("he's been extremely helpful with everything"), Summer Wagner ("she's amazing, and a wonderful artist"), and @redbeardnft ("he offers a lot of wonderful insight and makes me feel like I could be in good hands").

Artists inspiring him lately: Summer Wagner, Brooke DiDonato, and Ben Zank.

What does he wish people understood? That shooting at night doesn't mean horror. Darkness can be peaceful. Beautiful. Not everything shrouded is sinister.

He struggles with one more thing. Talking about his work.

"The most intelligent way I can express things is in this way. Through the art. And then when I open up my mouth, everything that comes out is just like a comprehension of a fifth grader."

He'd rather frame the work and let viewers experience it than risk diminishing it with clumsy words. Maybe someday, he says, after more practice, he'll find the language. For now, the priority is respecting what he's made.

"The most important part to me is respecting it."

For future Weekly Dose episodes, @briscoepark recommends @molly_mccutch, @brokedidonato, @summergwagner, and @ben_zank. Briscoe was recommended by the void. He emerged fully formed from Southern fog.